در میان هفت وادی عشق با داریوش دولتشاهی

گودرز اقتداری

ویژه ایران ما

در سالهای میانی دهه چهل شاید هشت یا نه ساله بودم که شبی میهمانی بزرگی در خانه مان برپا شد و برای نخستین بار صدای تار حرفه ای را شنیدم. پدرم در شهری دور افتاده رئیس بانک ملی بود. گاه گداری در دوره های روسا تار سلیمان خان شهردار را که تنها نوازنده شهر بود می شنیدیم که آنهم به ندرت اتفاق می افتاد. پدرم به تازگی ضبط صوت فیلیپسی خریده بود و از قدرت ضبط خود بسیار مفتخر و مشعوف بود. او در آن روزها در بین دوستانش معروفیت دیگری هم داشت که "آقای رئیس بانک برای هر چیزی فورا یک پوشش هم می سازد"، و صد البته ضبط صوت فیلیپس هم از این قائده مستثنا نبود و بزودی با یک پوشش ساتین آبی سلطنتی در گوشه میهمان خانه پنج دری جای خود را پیدا کرد.

در آن شب تابستان از طرفهای عصر چندین مرغ و جوجه را سر بریدند و دیگ های پلو را بر اجاق گذاشتند. میهمان آن شب نوازنده شهیر رادیو ملی ایران استاد لطف الله مجد بود. هنوز غروب نرسیده میهمان های همیشگی، آقایان روسا و همسرانشان، یکی پس از دیگری از راه رسیدند و به انتظار استاد نشستند. پاسی از شب نگذشته سرانجام استاد که از بستگان فرماندار بود هم به جمع پیوست و بزودی صدای نوش نوش بلند شد. بعداز شام وآنگاه که سرها گرم شد درخواست ها سرازیر شد که استاد هم افتخار بدهند و حاضرین را به سرپنجه شیرین شان مفتخر کنند. پدر هم اصرار داشت که اجازه داده شود این اجرا را ضبط نماید و استاد مجد هم رضایت داد مشروط بر آنکه او میکرفن را نبیند. این شرط به من که در پشت درب نشسته بودم اجازه ورود داد تا نگاهدار میکرفن باشم.

همه دور اتاق برروی پتو های ملافه شده ای نشسته و به دیوار های تازه رنگ شده تکیه داده بودند. چراغ ها خاموش شد و لطف الله خان پیش درآمد را آغاز کرد. چند دقیقه ای نگذشته استاد ناخودآگاه با ضربه های پایش شروع به حرکت کرد و میهمانان یکی یکی از سرراهش کنار رفته و در سکوت پشت سرش جای گرفتند. پایان فرود فرارسید و چراغ روشن شد. بر همه معلوم گشت که در جریان نواختن، استاد مضرابش را از دست داده و چنان در حال خویش بوده که با ناخن انگشتش ادامه داده بود که درآن لحظه خون چکان بود و قطرات سرخ رنگ آن بر ملحفه سفید نشسته.

آن نوار به عشق بقیه عمر پدرم بدل گشت ، چنانکه حتی در شب چهلم پدر هم به یادبود آنرا پخش کردیم. آن اجرا بسیار حزن انگیز و با احساس بود گویی استاد همه درد انگشت بریده را در موسیقی خویش نشانده باشد. من آن نوار را پیش از آنکه به تبعید خود خواسته بیایم بارها شنیده و اما با تمام زندگی و خاطرات در ایران به جای گذاشتم. دلم اما هم چنان برای شنیدن زخمه تار استاد تنگ می شد.

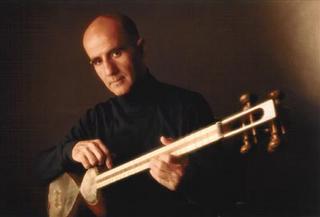

این دل تنگی را دوسه هفته قبل با شرکت در کنسرت دکتر داریوش دولتشاهی در شهر پرتلند اورگان به آرامش سپردم. دوست خوبم داریوش دکترای خود را در هنر موسیقی با تاکید در موسیقی الکترونیک از دانشگاه کلمبیا گرفته است و اما در دانشگاه تهران و کنسرواتوار موسیقی آمستردام و انستیتو صداشناسی اوترخت هم تحصیل کرده است. وی نیز هم چون من در شهر پرتلند می زید. اجراهای زنده داریوش بسیار نادر است و معدود. دقت و تکامل جویی اش مانع از آن می شود که این اجرا ها تکرار شوند ولذا هر کدام را به تجربه ای بی نظیر بدل می سازد، از آن نوع که در مقدمه این مقال گفتم.

این بار داریوش هفت شهر عشق را بداهه نواخت و فرامرز مهردادفر و پوریا صیرفی در این برنامه او را همراه بودند. قطعه بر اساس منطق الطیر عطار نوشته شده و از شش موومان تشکیل یافته است: طلب و عشق، معرفت، استغنا، توحید، حیرت،و سرانجام فقر و فنا. در سفر عشق استاد از هفت وادی می گذرد و با نغمه سازش سی و گاه هزاران مرغ را به پرواز می آورد تا هم چون من و تو و خود هنر مند در جستجوی سیمرغ و ذات خویش ره بسپاریم. در میان گردبادی همه مان به پی گیر خویش در هفت وادی می چرخیم، هریک به گوشه ای وا می افتیم و در هر پیچ راه تنی چند جان برسر مقصود می نهیم. استاد با زخم تار خویش و گاه با عتاب چند مرغ را از کاروان می راند و به دره های خوفناک پرتاب می کند. پژواک صدای زجه مرغان با حزن موسیقی می آمیزد اما زخمه ی استاد را سر بازایستادن نیست. سرانجام اندکی به وادی هفتم می رسند و استاد، آزاد از سنت پاگیر دستگاه های موسیقی، بی شبهه یکی شان.

پایانه بی شک از زیباترین موومان ها است رنگین و اعجاب انگیز با آینه هایی دورادور که از انعکاس تصویر مرغکان، قطرات خون بر پرهای سپیدشان، ابدیتی آفریده اند. تو گویی مضراب استاد باز هم گم شده باشد و ما نیز.

با دکتر دولتشاهی از طریق تارنمای ایشان در www.dolat-shahi.com می توان تماس گرفت

.

Read more! □ نوشته شده در ساعت 9:36 PM توسط qAsedak

گودرز اقتداری

ویژه ایران ما

در سالهای میانی دهه چهل شاید هشت یا نه ساله بودم که شبی میهمانی بزرگی در خانه مان برپا شد و برای نخستین بار صدای تار حرفه ای را شنیدم. پدرم در شهری دور افتاده رئیس بانک ملی بود. گاه گداری در دوره های روسا تار سلیمان خان شهردار را که تنها نوازنده شهر بود می شنیدیم که آنهم به ندرت اتفاق می افتاد. پدرم به تازگی ضبط صوت فیلیپسی خریده بود و از قدرت ضبط خود بسیار مفتخر و مشعوف بود. او در آن روزها در بین دوستانش معروفیت دیگری هم داشت که "آقای رئیس بانک برای هر چیزی فورا یک پوشش هم می سازد"، و صد البته ضبط صوت فیلیپس هم از این قائده مستثنا نبود و بزودی با یک پوشش ساتین آبی سلطنتی در گوشه میهمان خانه پنج دری جای خود را پیدا کرد.

در آن شب تابستان از طرفهای عصر چندین مرغ و جوجه را سر بریدند و دیگ های پلو را بر اجاق گذاشتند. میهمان آن شب نوازنده شهیر رادیو ملی ایران استاد لطف الله مجد بود. هنوز غروب نرسیده میهمان های همیشگی، آقایان روسا و همسرانشان، یکی پس از دیگری از راه رسیدند و به انتظار استاد نشستند. پاسی از شب نگذشته سرانجام استاد که از بستگان فرماندار بود هم به جمع پیوست و بزودی صدای نوش نوش بلند شد. بعداز شام وآنگاه که سرها گرم شد درخواست ها سرازیر شد که استاد هم افتخار بدهند و حاضرین را به سرپنجه شیرین شان مفتخر کنند. پدر هم اصرار داشت که اجازه داده شود این اجرا را ضبط نماید و استاد مجد هم رضایت داد مشروط بر آنکه او میکرفن را نبیند. این شرط به من که در پشت درب نشسته بودم اجازه ورود داد تا نگاهدار میکرفن باشم.

همه دور اتاق برروی پتو های ملافه شده ای نشسته و به دیوار های تازه رنگ شده تکیه داده بودند. چراغ ها خاموش شد و لطف الله خان پیش درآمد را آغاز کرد. چند دقیقه ای نگذشته استاد ناخودآگاه با ضربه های پایش شروع به حرکت کرد و میهمانان یکی یکی از سرراهش کنار رفته و در سکوت پشت سرش جای گرفتند. پایان فرود فرارسید و چراغ روشن شد. بر همه معلوم گشت که در جریان نواختن، استاد مضرابش را از دست داده و چنان در حال خویش بوده که با ناخن انگشتش ادامه داده بود که درآن لحظه خون چکان بود و قطرات سرخ رنگ آن بر ملحفه سفید نشسته.

آن نوار به عشق بقیه عمر پدرم بدل گشت ، چنانکه حتی در شب چهلم پدر هم به یادبود آنرا پخش کردیم. آن اجرا بسیار حزن انگیز و با احساس بود گویی استاد همه درد انگشت بریده را در موسیقی خویش نشانده باشد. من آن نوار را پیش از آنکه به تبعید خود خواسته بیایم بارها شنیده و اما با تمام زندگی و خاطرات در ایران به جای گذاشتم. دلم اما هم چنان برای شنیدن زخمه تار استاد تنگ می شد.

این دل تنگی را دوسه هفته قبل با شرکت در کنسرت دکتر داریوش دولتشاهی در شهر پرتلند اورگان به آرامش سپردم. دوست خوبم داریوش دکترای خود را در هنر موسیقی با تاکید در موسیقی الکترونیک از دانشگاه کلمبیا گرفته است و اما در دانشگاه تهران و کنسرواتوار موسیقی آمستردام و انستیتو صداشناسی اوترخت هم تحصیل کرده است. وی نیز هم چون من در شهر پرتلند می زید. اجراهای زنده داریوش بسیار نادر است و معدود. دقت و تکامل جویی اش مانع از آن می شود که این اجرا ها تکرار شوند ولذا هر کدام را به تجربه ای بی نظیر بدل می سازد، از آن نوع که در مقدمه این مقال گفتم.

این بار داریوش هفت شهر عشق را بداهه نواخت و فرامرز مهردادفر و پوریا صیرفی در این برنامه او را همراه بودند. قطعه بر اساس منطق الطیر عطار نوشته شده و از شش موومان تشکیل یافته است: طلب و عشق، معرفت، استغنا، توحید، حیرت،و سرانجام فقر و فنا. در سفر عشق استاد از هفت وادی می گذرد و با نغمه سازش سی و گاه هزاران مرغ را به پرواز می آورد تا هم چون من و تو و خود هنر مند در جستجوی سیمرغ و ذات خویش ره بسپاریم. در میان گردبادی همه مان به پی گیر خویش در هفت وادی می چرخیم، هریک به گوشه ای وا می افتیم و در هر پیچ راه تنی چند جان برسر مقصود می نهیم. استاد با زخم تار خویش و گاه با عتاب چند مرغ را از کاروان می راند و به دره های خوفناک پرتاب می کند. پژواک صدای زجه مرغان با حزن موسیقی می آمیزد اما زخمه ی استاد را سر بازایستادن نیست. سرانجام اندکی به وادی هفتم می رسند و استاد، آزاد از سنت پاگیر دستگاه های موسیقی، بی شبهه یکی شان.

پایانه بی شک از زیباترین موومان ها است رنگین و اعجاب انگیز با آینه هایی دورادور که از انعکاس تصویر مرغکان، قطرات خون بر پرهای سپیدشان، ابدیتی آفریده اند. تو گویی مضراب استاد باز هم گم شده باشد و ما نیز.

با دکتر دولتشاهی از طریق تارنمای ایشان در www.dolat-shahi.com می توان تماس گرفت

.

Read more! □ نوشته شده در ساعت 9:36 PM توسط qAsedak

Through the Seven Valleys of the Way with Dariush Dolat-shahi;

Goudarz Eghtedari

special for Iranian.com

I was 8 or 9 years old, in the mid ‘60s, when one night a large party brought the sounds of professional Tar to our house. My father was a bank manager in the remote town of Sirjan. Once in a while in roassa’s doreh one could hear the Tar of Soleiman Khane Daragahi, the mayor, the only tar player in town. In those days my dad had just purchased a Philips reel tape player and was very proud of his recording capabilities. He was famous for making a cover for everything and this humongous machine was no exception: a blue satin cover was made for it and sat in our mehmankhaneh. That night our guest was supposed to be a famous Tar player, who played for Iranian National Radio, the late Ustad Lotfollah Majd.

Before sunset several chicken were slaughtered and rice was on the ojagh in preparation of dinner, well in advance. Several of the usual suspects arrived early that night and finally the artist, a guest of the governor, showed up. Before long, bottles of aragh keshmesh and vodka were opened and sounds of noush noush could be noted. After dinner and once most heads were a little warm, the requests started that Ustad Majd should give the honor of offering some music to those present. My Dad insisted on recording and Lotfollah Khane Majd agreed as long as he could not see the microphone. That was an opportunity for me to enter the scene and be the guardian of the microphone. Every one was sitting on the floor on blankets next to white walls--this was years before wall paper came to town. The lights were turned off and Ustad started playing. Soon after, he started moving around the room and every one would change their seat to open space for Ustad who was unconsciously circling the room. Later that night when the lights came back, we noticed drops of blood all over the white sheeted blanket. Ustad had lost his mezraab, but had decided not to stop and had played with his nail, with a finger that was bleeding by now. That recording became the love of my dad’s life and I played it at his memorial. I thought it was a very saddening and powerful performance, as if Ustad Majd had put all the pain of his injured finger into the music. I have listened to that tape numerous times until I left my homeland with all the memories, including the royal blue satin covered Philips. I have missed the zakhmehye tar of Ustad Majd ever since.

That is until last Monday when I attended Dariush Dolat-shahi’s concert in Portland, Oregon. Dariush, a good friend, has gained his Doctor of Musical Art degree in music composition and electronic music from Columbia University. He has studied at Tehran University, as well as at the Amsterdam Conservatory of Music and Utrecht Institute of Sonology in the Netherlands. He lives in Portland.

Dariush’s live performances are very rare and sacred to attend. His perfectionism and high expectations make the performances difficult to repeat, and turns them into unique experiences of the kind I described in the opening of this story. This time Dariush performed his Seven Valleys of the Way, a composition influenced by the twelfth century Persian philosopher and Sufi poet Farid ud-din Attar and his major work of poetry The Conference of the Birds (mantiq ut-tair)*. The composition consists of six movements representing the seven valleys; the Quest, the Love, the Insight into Mystery, Detachment, Unity, Bewilderment, and the finale of the Poverty and Nothingness. As the Ustad travels through the valleys, his instrument turns into waves of thirty birds and sometimes millions of them in search of themselves. You and me and the artist, we are all whirling in the valleys in a faithful search of the divine Simorgh. Thousands of us perish during the sacred journey which requires faith but does not guarantee the outcome. Enlightenment requires discipline, self examination and self-awareness, and the purging of the spirit, as Attar makes clear. At each corner of the forth valleys Ustad detaches one or many of birds with a zakhmeye tar and drops them into their dark destiny, he beats the tar angrily to get rid of the unfaithful. Cries, the sadness of the tunes, breaks the heart and injures each being but do not seem to stop him. Only a few arrive at the finale of the Poverty and Nothingness, the Ustad for sure is one of them finding himself freed of traditional Persian dastgahs. The finale is the most colorful movement with mirrors all around reflecting all the remaining birds, blood stains on their white feathers. The Ustad’s mezraab must have been lost again, and so do we.

Dr. Dariush Dolat-shahi can be reached at www.dolat-shahi.com and his new CDs will be available at Amazon.com very soon.

* The Conference of the Birds recounts the story of the birds of the world gathering together to meet the Simurgh or the King of birds. The birds choose a guide from among themselves – the hoopoe, who represents the spiritual master and makes up the Tariqah (Way). The hoopoe tells them that the Simurgh lives in a distant place and the journey to him is difficult. The birds have to cross seven valleys on the fateful journey to the divine Simurgh.

The Valley of the Quest

The Valley of Love

The Valley of Insight into Mystery

The Valley of Detachment

The Valley of Unity

The Valley of Bewilderment

The Valley of Poverty and Nothingness

Thousands of birds perish during the journey; they make the right choice to search for the Simurgh, but they are not guaranteed success. Attar makes it clear that simply to wish to be united with the Divine is not in itself enough. Enlightenment requires discipline, self-examination and self-awareness, and the purging of the spirit.

The birds arrive at the court of the Simurgh. At first they are turned back; but then are finally admitted, only to see the reflection of themselves in a mirror. They learn that the Simurgh they have sought is none other than themselves. Only thirty (si) birds (murgh) are left at the end of the Way, the Si-murghs meet the Simurgh, the goal of their quest.

Goudarz Eghtedari

special for Iranian.com

I was 8 or 9 years old, in the mid ‘60s, when one night a large party brought the sounds of professional Tar to our house. My father was a bank manager in the remote town of Sirjan. Once in a while in roassa’s doreh one could hear the Tar of Soleiman Khane Daragahi, the mayor, the only tar player in town. In those days my dad had just purchased a Philips reel tape player and was very proud of his recording capabilities. He was famous for making a cover for everything and this humongous machine was no exception: a blue satin cover was made for it and sat in our mehmankhaneh. That night our guest was supposed to be a famous Tar player, who played for Iranian National Radio, the late Ustad Lotfollah Majd.

Before sunset several chicken were slaughtered and rice was on the ojagh in preparation of dinner, well in advance. Several of the usual suspects arrived early that night and finally the artist, a guest of the governor, showed up. Before long, bottles of aragh keshmesh and vodka were opened and sounds of noush noush could be noted. After dinner and once most heads were a little warm, the requests started that Ustad Majd should give the honor of offering some music to those present. My Dad insisted on recording and Lotfollah Khane Majd agreed as long as he could not see the microphone. That was an opportunity for me to enter the scene and be the guardian of the microphone. Every one was sitting on the floor on blankets next to white walls--this was years before wall paper came to town. The lights were turned off and Ustad started playing. Soon after, he started moving around the room and every one would change their seat to open space for Ustad who was unconsciously circling the room. Later that night when the lights came back, we noticed drops of blood all over the white sheeted blanket. Ustad had lost his mezraab, but had decided not to stop and had played with his nail, with a finger that was bleeding by now. That recording became the love of my dad’s life and I played it at his memorial. I thought it was a very saddening and powerful performance, as if Ustad Majd had put all the pain of his injured finger into the music. I have listened to that tape numerous times until I left my homeland with all the memories, including the royal blue satin covered Philips. I have missed the zakhmehye tar of Ustad Majd ever since.

That is until last Monday when I attended Dariush Dolat-shahi’s concert in Portland, Oregon. Dariush, a good friend, has gained his Doctor of Musical Art degree in music composition and electronic music from Columbia University. He has studied at Tehran University, as well as at the Amsterdam Conservatory of Music and Utrecht Institute of Sonology in the Netherlands. He lives in Portland.

Dariush’s live performances are very rare and sacred to attend. His perfectionism and high expectations make the performances difficult to repeat, and turns them into unique experiences of the kind I described in the opening of this story. This time Dariush performed his Seven Valleys of the Way, a composition influenced by the twelfth century Persian philosopher and Sufi poet Farid ud-din Attar and his major work of poetry The Conference of the Birds (mantiq ut-tair)*. The composition consists of six movements representing the seven valleys; the Quest, the Love, the Insight into Mystery, Detachment, Unity, Bewilderment, and the finale of the Poverty and Nothingness. As the Ustad travels through the valleys, his instrument turns into waves of thirty birds and sometimes millions of them in search of themselves. You and me and the artist, we are all whirling in the valleys in a faithful search of the divine Simorgh. Thousands of us perish during the sacred journey which requires faith but does not guarantee the outcome. Enlightenment requires discipline, self examination and self-awareness, and the purging of the spirit, as Attar makes clear. At each corner of the forth valleys Ustad detaches one or many of birds with a zakhmeye tar and drops them into their dark destiny, he beats the tar angrily to get rid of the unfaithful. Cries, the sadness of the tunes, breaks the heart and injures each being but do not seem to stop him. Only a few arrive at the finale of the Poverty and Nothingness, the Ustad for sure is one of them finding himself freed of traditional Persian dastgahs. The finale is the most colorful movement with mirrors all around reflecting all the remaining birds, blood stains on their white feathers. The Ustad’s mezraab must have been lost again, and so do we.

Dr. Dariush Dolat-shahi can be reached at www.dolat-shahi.com and his new CDs will be available at Amazon.com very soon.

* The Conference of the Birds recounts the story of the birds of the world gathering together to meet the Simurgh or the King of birds. The birds choose a guide from among themselves – the hoopoe, who represents the spiritual master and makes up the Tariqah (Way). The hoopoe tells them that the Simurgh lives in a distant place and the journey to him is difficult. The birds have to cross seven valleys on the fateful journey to the divine Simurgh.

The Valley of the Quest

The Valley of Love

The Valley of Insight into Mystery

The Valley of Detachment

The Valley of Unity

The Valley of Bewilderment

The Valley of Poverty and Nothingness

Thousands of birds perish during the journey; they make the right choice to search for the Simurgh, but they are not guaranteed success. Attar makes it clear that simply to wish to be united with the Divine is not in itself enough. Enlightenment requires discipline, self-examination and self-awareness, and the purging of the spirit.

The birds arrive at the court of the Simurgh. At first they are turned back; but then are finally admitted, only to see the reflection of themselves in a mirror. They learn that the Simurgh they have sought is none other than themselves. Only thirty (si) birds (murgh) are left at the end of the Way, the Si-murghs meet the Simurgh, the goal of their quest.

Read more! □ نوشته شده در ساعت 9:30 PM توسط qAsedak

قاصدک هان چه خبر آوردی؟

از کجا وزچه خبر آوردی؟

خوش خبر باشی اما

گرد بام و در من بی ثمر می گردی.

انتظار خبری نیست مرا

......

My radio show: VOME

My Daughter's Blog

AIFC web site

Global Alien

EJI web site

BBC Persian

Deutsche Welle

Previous Posts

- https://v.ht/TC0L goudarz

- re:

- COME JOIN IN AN ALL-OUT DEMONSTRATION OF OUR COM...

- The Hostage Crisis, a revisitيادمان اشغال سفارت آم...

- Political Chain Murders of Iranیازدهمین سال قتلهای...

- A review of Alavi Foundation from its birth until ...

- Ustad Shajarian and his Gun, a reflection on non-v...

- Situation of Iran's People Mujahedin(MEK)at Camp A...

- Iranian non violent resistance and reactionaries -...

- How can we help the movement from abroad - چگونگي ...

Archives

- 12/29/2002 - 01/05/2003

- 02/02/2003 - 02/09/2003

- 04/06/2003 - 04/13/2003

- 06/01/2003 - 06/08/2003

- 06/29/2003 - 07/06/2003

- 07/13/2003 - 07/20/2003

- 08/31/2003 - 09/07/2003

- 11/09/2003 - 11/16/2003

- 11/16/2003 - 11/23/2003

- 11/30/2003 - 12/07/2003

- 05/23/2004 - 05/30/2004

- 10/31/2004 - 11/07/2004

- 12/05/2004 - 12/12/2004

- 01/02/2005 - 01/09/2005

- 04/03/2005 - 04/10/2005

- 05/29/2005 - 06/05/2005

- 06/05/2005 - 06/12/2005

- 06/19/2005 - 06/26/2005

- 06/26/2005 - 07/03/2005

- 08/07/2005 - 08/14/2005

- 08/14/2005 - 08/21/2005

- 10/23/2005 - 10/30/2005

- 01/15/2006 - 01/22/2006

- 01/29/2006 - 02/05/2006

- 02/12/2006 - 02/19/2006

- 02/19/2006 - 02/26/2006

- 02/26/2006 - 03/05/2006

- 03/19/2006 - 03/26/2006

- 07/30/2006 - 08/06/2006

- 10/08/2006 - 10/15/2006

- 12/03/2006 - 12/10/2006

- 02/18/2007 - 02/25/2007

- 06/03/2007 - 06/10/2007

- 09/09/2007 - 09/16/2007

- 10/07/2007 - 10/14/2007

- 10/14/2007 - 10/21/2007

- 11/23/2008 - 11/30/2008

- 01/24/2010 - 01/31/2010

- 05/28/2017 - 06/04/2017

- 09/08/2019 - 09/15/2019

- 05/10/2020 - 05/17/2020